What Changed In The Industrial Union Movement In The 1930s?

Strikes & Unions

Timber workers went on strike for ameliorate conditions and the legal recognition of their union in 1935. (Photo courtesy of the University of Washington Library, Special Collections)

Depressions oft break unions. Equally unemployment soared in the early years of the 1930s, the labor movement seemed helpless, unable to protect jobs let alone wage rates. But even before the starting time hints of economic recovery, there were signs of the surge of militant union building to come. The Keen Depression would ultimately be remembered equally labor's finest hour, a time of massive organizing drives, successful strikes, soaring social idealism, and political campaigns that changed labor law for hereafter generations. By the stop of the 1930s most Americans realized that unions were one of the keys to 18-carat democracy.

Washington State had long understood unions. The Knights of Labor had been active in Seattle, Tacoma, and Spokane in the 1880s but were presently eclipsed past unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL). During the first two decades of the twentieth century there were few cities in the United States more tightly unionized than Seattle.

Anybody from carpenters and street motorcar conductors to waitresses and newsboys belonged to a wedlock. In 1919, when Seattle unions gained worldwide headlines by declaring a general strike that shut downward the metropolis for five days, some 60,000 workers belonged to 110 unions affiliated with the Seattle Primal Labor Council and the Washington Country Federation of Labor. Other cities-- Tacoma, Everett, Bellingham, and Spokane--besides knew the strength of organized labor, as did railroad and mining towns throughout the state. The Industrial Workers of the Earth (IWW) had offered a more radical alternative to the AFL, and had been briefly effective among timber workers and farm workers until federal authorities moved to suppress them during World War I.

Pass up 1929-1933

Labor Events Yearbook

Explore a twenty-four hour period-by-day database of more than 600 strikes, protests, campaigns, and labor political initiatives occurring in the land of Washington from 1930 through 1938, culled from state labor newspapers.

Explore a twenty-four hour period-by-day database of more than 600 strikes, protests, campaigns, and labor political initiatives occurring in the land of Washington from 1930 through 1938, culled from state labor newspapers.

Some of labor'south force had been lost in the 1920s, a decade dominated by bourgeois Republicans and business boosterism both in Washington DC and Washington Land. The price increased during the initial years of the Depression. Union membership in the state declined, but it is hard to tell how much since unions were disinclined to publicize their weakness. Strikes became rare between 1930 and 1933. The Washington State Labor News mentioned merely a few modest and brusque walkouts. (See Labor Yearbook).

The AFL unions turned to politics, seeking legislation to protect wage levels and wedlock jobs. The Seattle Primal Labor Quango spent the early months of 1931 candidature for a charter amendment that would have made the five-day week mandatory for metropolis employees, thus spreading out scarce work. But voters, worried either most taxes or about funds to feed the unemployed, rejected it. A few months later on, the labor movement rejoiced when conservative mayor Frank Edwards lost a recollect election and still more when the City Council named former labor leader Robert Harlin as temporary replacement. But Harlin proceeded to lose favor with voters by appearing to intendance more about spousal relationship wage rates than about the thousands of desperate unemployed. He lost his bid for a total term in leap 1932.

While matrimony leaders had go cautious and ineffective, a new labor motion was taking shape among the unemployed. In 1931, socialists living in W Seattle launched the Unemployed Citizens League to demand jobs and services. The arrangement quickly spread and within months claimed upwards of 20,000 members in dozens of neighborhood UCL clubs spread throughout Seattle and other Puget Audio cities. Information technology was the UCL, not the AFL unions, that forced Mayor Edwards out of part. And it was the UCL radicals and a smaller cadre of Communists who would prepare the stage for the revival of union organizing.

Rebuilding 1934-1936

Tacoma and Seattle longshoremen lead a strikebreaker, identified as 'Iodine' Harradin, off the Seattle docks during 1934 strike. Harradin and other strikebreakers were removed under a flag of truce equally constabulary stood dorsum. (Port of Seattle photo. Ronald East. Magden Collection.)

The National Industrial Recovery Act, one of the New Deal programs created by Roosevelt and Congress in 1933, included an important new set of rights. Workers would take, for the first fourth dimension, the right to join unions. Armed with that slogan, activists fix out to rebuild former unions and create new ones. Across the nation, 1934 saw huge organizing campaigns followed past major strikes. In Washington, campaigns began in many industries, about importantly on the waterfront and among truck drivers.

The single most of import strike of the decade began on May 9, 1934 when longshoremen in Washington joined their counterparts in Oregon and California in a walkout that would shut downward ports from Bellingham to San Diego for eighty-iii days, freezing trade along the coast while creating a supply crisis for Alaska and Hawaii. Before it was over, San Francisco would endure a general strike while Seattle witnessed pitched battles betwixt strikers and police and at least one union death. The state of war on the docks proved to exist a victory for the newly reconstituted longshoreman's union and a victory for unionism on the West Declension.

The 1934 waterfront strike inspired a wave of organizing and strikes: amongst Teamsters, who turned a union that had been stiff in Seattle into a spousal relationship that represented truckers from Mexico to the Canadian border; among loggers and sawmill workers; amid sailors, stewards, pilots, tugboatmen, and other maritime workers; amongst Filipino cannery workers; and many, many others.

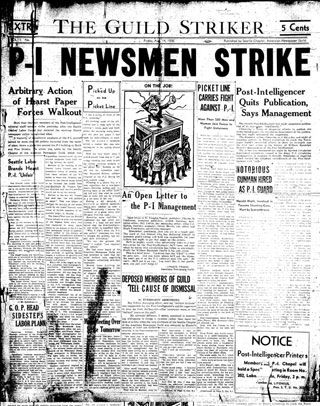

The Society Striker was the official paper of the 1936 Newspaper Guild strike against the Seattle P-I.

The Society Striker was the official paper of the 1936 Newspaper Guild strike against the Seattle P-I.

Ane key achievement was the Seattle newspaper strike of 1936. Journalists were white-neckband workers, thus not usually union material. But the American Newspaper Guild had built a base in Seattle'due south paper rooms, including 35 members employed by the Seattle Mail-Intelligencer, owned by paper tycoon William Randolph Hearst. When Hearst refused to negotiate, the writers walked out and quickly won the back up of all the unions in Seattle, including the now powerful Teamsters. 3 and a half months after Hearst settled, giving the Newspaper Social club its first victory and cementing Washington'southward reinvigorated reputation as a state where labor had genuine ability.

Labor's ceremonious war

In 1935, Congress passed the National Labor Relations Act, reaffirming the promises of the NIRA and establishing boosted rights for workers and unions. That year at the convention of the American Federation of Labor the revived labor motion began to split apart. John Fifty. Lewis, president of the United Mine Workers, called for a new strategy. Unions should be organized on the basis of industry rather than on the basis of arts and crafts, which alllowed for the more inclusive organization of nonwhite workers, women workers, and the unskilled. When the proposal was voted down, the UMW and iii other unions went alee on their own, launching what would get in 1937 the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a second labor federation dedicated to industrial organizing.

The split turned into what some called "labor'due south civil war," as unions sorted themselves into rival federations and fought over members and contracts. In Washington, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters anchored the AFL while the longshoremen, newly renamed the International Longshoremen and Warehousemen'due south Marriage (ILWU), anchored the CIO.

The aircraft workers building planes for the Boeing Visitor became one of the prizes in this contest. In 1936 Boeing landed a contract for an innovative bomber that would get the work horse of Earth War II-- the B-17. The company quickly expanded facilities and with equal dispatch signed a contract with the International Clan of Machinists, an AFL wedlock.

The Timber Worker paper was developed past workers in Aberdeen, Washington in the midst of the 1935 strike. It served as a vox for timberworkers and sought to annul the negative bias of Seattle's established media.

The CIO won its big prize in the woods. Timber and sawmill workers who had organized in 1935 with a dramatic strike centered in Tacoma were initially affiliated with the United Alliance of Carpenters and Joiners, an AFL spousal relationship. But in 1937, the 70,000 woodworkers bolted, joining the CIO and renaming their union the International Woodworkers of America (IWA).

The CIO and the AFL competed over members and also offered competing visions of what unions should do. The CIO faulted the AFL unions for excluding nonwhites and sometimes women and for their small-scale, if not actually bourgeois goals. Well-nigh of the CIO unions practiced "social motion unionism," advocating an array of social justice programs that included expansive economic rights and also equal political and social rights for minorities. Civil rights was 1 of the important commitments of the CIO. The AFL charged that the CIO unions were dominated by Reds, were as well interested in radical ideas, and that the rival federation weakened what should accept been the united front of labor.

In truth the political differences were not as keen as they seemed. Both labor bodies supported the Autonomous Political party and worked together on many political campaigns. Although they fought bitterly over some bug, both pushed for reforms that would strengthen the social condom net (including calling for national health insurance). Neither was actually conservative nor actually Communist controlled.

Labor Culture

Members of the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union march in the 1939 Seattle Labor Day Parade (courtesy Fred and Dorothy Cordova and the Filipino American National Historical Club)

Past the last years of the 1930s organized labor--despite its divisions--was stronger and enjoyed more than legitimacy than possibly at any time earlier or since. On Labor Day in 1937, the unions in Seattle put on dramatic display. Every bit 60,000 spectators lined the streets, marriage later marriage paraded in organized, banner carrying units--30,000 marchers in all. The parade carried the message that Seattle was once once more a proud wedlock town, as were many other locales.

Unions took on new meanings in the 1930s. They represented not but better wages and working atmospheric condition just a new mensurate of commonwealth. Americans of many backgrounds now believed that the right to vote was not enough, that rights should also extend to the piece of work place. Employers should not have absolute power. Workers too deserved a phonation and collective bargaining would provide information technology.

Joining unions thus become the smart, respectable, and democratic matter to do. And not merely for blue-collar workers. Teachers were starting unions. Retail clerks at Nordstroms and other stores bargained contracts. Cab drivers had organized and the Culinary Workers Union, representing waiters, waitresses, and bar tenders, had nearly 5,000 members.

Two other unions show the new faith in collective bargaining as a autonomous right. The Works Progress Assistants had been established to provide temporary jobs to unemployed men and women who could not notice piece of work in the private sector. The Workers Alliance, a national organization led by Socialists and Communists, appear that it would serve every bit the union for WPA workers. Nowhere was the Workers Alliance more than successful than in Washington State. Demanding that WPA officials concord to collective bargaining, the Washington branch of the Workers Brotherhood initiated a walkout in January 1937. It speedily spread across the state, ultimately involving 5,000 WPA workers and shutting down 30 dissimilar projects. After ii weeks, during which other unions made clear their support, WPA administrators agreed to bargain.

Even more revealing of the breadth of labor civilisation was the One-time-Age Pension Spousal relationship, formed in 1937 to serve as the bargaining agent for elderly Washingtonians who were eligible for a small pension under the state'due south social security law. The Pension Spousal relationship was dramatically successful. Thousands joined, supporting the PU demand for bargaining rights and for a guaranteed minimum of $30 every month. King Canton officials were the first to recognize the new matrimony, followed by other counties and also by state government. The Pension Union went on to become a major force in Washington politics, successfully lobbying for college benefits and in the 1940s passing election measures to insure that the elderly received adequate back up.

The Nifty Depression had initially humbled the land's unions, but in the cease it helped them grow and change. This was the era that inverse labor law and put in place expectations about rights and social guarantees that survive today. It was also the era that congenital the mod labor movement.

Copyright (c) 2009, James Gregory

Side by side: Politics

Click on the links beneath to read illustrated research reports on strikes and unions during Washington State's Smashing Depression:

| Communism, Anti-Communism, and Kinesthesia Unionization: The American Federation of Teachers' Union at the Academy of Washington, 1935-1948, by Andrew Knudsen The founding of an AFT-affiliated faculty union at the University of Washington allowed faculty chore security and redress during the economic crisis. Notwithstanding the radical and sometimes Communist politics of its members made the union susceptible to federal anti-Communist repression by the 1940s. |

| The Voice of Activity: A Paper for Workers and the Disenfranchised, by Seth Goodkind The Vox of Action was a radical labor newspaper published in Seattle between 1933 and 1936. This newspaper traces its never-official links to the politics of the Communist Party and its commitments to workers and the unemployed. |

| A Worker's Commonwealth Confronting Fascism: The Vox of Activeness'southward Idealized Pictures of Soviet Russia in the 1930s, by Elizabeth Poole The Vocalisation of Action portrayed Soviet Russia as a model for an antifascist workers' republic. |

| Depression-Era Civil Rights on Trial: The 1933 Battle of Congdon Orchards in the Yakima Valley," by Mike DiBernardo The Industrial Workers of the World had led the system of farmworkers in Washington's Yakima Valley. On August 24, 1933, strikers faced 250 farmers, organized as a militia to put downwardly the incipient matrimony organizing among fieldworkers. |

| The Seattle Press and the 1934 Waterfront Strike, by Rachelle Byarlay The 1934 longshore strike up and downwards the West Coast was one of the most explosive and successful strikes during the Depression. An assay of iii Seattle newspapers hither shows the shifts in news coverage for and against the strike. |

| The Murders of Virgil Duyungan and Aurelio Simon and the Filipino Cannery Workers' Union, past Nicole Dade In 1936, ii leaders of the Filipino Cannery Workers' and Farm Labor Spousal relationship were shot to death, weakening the marriage but likewise providing the fragmented Filipino community with a cause to unite behind. |

| The Timber Workers' Strike of 1935: Anti-Labor Bias in The Seattle Star, by Kristin Ebeling As the timber workers' 1935 strike became more and more controversial, The Seattle Star became less supportive in their coverage of the event, leading workers' to develop their own paper. |

| Labor's Great War on the Seattle Waterfront: A History of the 1934 Longshore Strike, by Rod Palmquist A multi-part in-depth essay, drawing from rare archives, of the 1934 longshore strike in Seattle and Tacoma. |

| Special Section: 1934 -- The Nifty Strike A special department of the Waterfront Workers History Project, with photographs, films, research reports, and documents from the strike. |

| The 1933 Boxing at Congdon Orchards, by Oscar Rosales Castañeda The 1933 boxing between organizing farmworkers and farm owners was part of a long history of farmworker organizing in Washington's Yakima Valley, as well as efforts by radicals to form unions in the region. |

| Gild Daily, newspaper written report by Erika Marquez The striking employees of the Seattle Mail Intelligencer, produced The Guild Daily during the 105 twenty-four hours strike against the Hearst-owned newspaper in 1936. |

| Timber Worker, newspaper study past Geraldine Carroll and Michael Moe Born in the midst of the 1935 timber strike, the Timber Worker was the union newspaper of the International Woodworkers of America, based in Aberdeen, WA. |

| The Pacific Declension Longshoremen, newspaper written report by Kristen Ebeling The Longshoremen began one year after the 1934 longshore strike, as the official newspaper of the International Longshoremen's Clan. |

| Aero Mechanic, paper study past Julian Laserna The phonation of Boeing workers in Local 751 of the International Association of Machinists, Aero Mechanic was founded in 1939 and has been published e'er since. |

| Bellingham Labor News, newspaper report past Jordan Van Vleet Established in 1939, The Bellingham Labor News was the official publication of the Bellingham Key Labor Council. It was published weekly until 1968 when information technology merged with other Northwest labor newspapers to become the Northwest Washington Labor News. |

| Organizing Unions: The '30s and '40s, past Brian Grijalva This paper traces the Washington Communist Political party'south attempts--and successes--in organizing unions during the 1930s and 1940s. |

| Harold Pritchett: Communism and the International Woodworkers of America, by Timothy Kilgren Pritchett, a Communist, became president of the combative timber union on the West Coast, but was eventually denied re-entry to the United states of america because of his scarlet politics. |

What Changed In The Industrial Union Movement In The 1930s?,

Source: https://depts.washington.edu/depress/strikes_unions.shtml

Posted by: motteavelifire1986.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Changed In The Industrial Union Movement In The 1930s?"

Post a Comment